To Build a Paradise In Hell: A Coronavirus Memoir.

As befit a virus that strikes silently, coronavirus entered our collective consciousness slowly, and then in an avalanche.

I don’t recall the first time I had heard the name. I had likely encountered it in my daily scroll of the news—something about an outbreak in Wuhan. It was surely significant and dreadful, but it would never impact me. At the time, I was busy organizing the Stanford Viennese Ball while balancing a strenuous Winter Quarter schedule. My most immediate health concern was a perpetual ringing and dullness in my right ear, after I had gone swimming a week earlier and waterlogged it.

Then, a few days before the Ball happened on February 1, emails and messages rolled in. Concerned attendees to the Ball began sending messages to the Viennese Ball Facebook page, to the Eventbrite email address, to me personally.

…the outbreak of coronavirus, as you may have heard, has reached to a level of global health emergency. Just today US government announced a travel ban…

I suggest that the Viennese Ball send out an alert to all participating students, distribute masks at the bus, and do temperature checks before the students board the bus and enter the entrance of the ball. This…has been the practice of the Chinese lunar new year gala.

The messages were a source of intense controversy on the organizing committee. We were faced with the logistical and financial impossibility of acquiring over a thousand pairs of gloves and masks in a single weekend. We did not have the manpower, training, or raw medical equipment to perform temperature checks, as one of the messages had recommended. We had little information about the virus itself—other than the fact that symptoms closely resembled the cold and flu—and were worried that we would unnecessarily turn people away. At the time, it was difficult to gauge the seriousness of the illness and effectively weigh our options. The virus still felt like a distant concern, far overshadowed by immediate deadlines: payments to vendors. Last instructions to volunteers. Tweaks in the final schedule. Amidst all of this, we did not want to sow seeds of mass panic, and overwhelm an already thinly-stretched committee with refund requests and questions we could not answer.

Within my committee, I navigated what might best be described as volatile terrain. Generally, opinions fell across two ends of a spectrum: on one end, people believed that coronavirus was a superfluous concern, and an unknown variable at best; the messages that we received had proposed unrealistic changes, and (in an extreme version of the view) disrespected the stress we were undergoing. At the time, we also saw little reason for extreme concern. As of January 31, only one case had been confirmed in Santa Clara County; the University had said almost nothing, and passed no official restrictions on large events. On the other end of the spectrum, some believed that coronavirus could be a legitimate concern, and that perhaps we should seek out some of the limited actions within our power.

I leaned slightly towards the latter camp, but realized I needed to tread the lines carefully. I proposed sending some sort of notice to our attendees, but the subject was so divisive within the committee that I ended up sending a general advisory about washing hands and good hygiene, never mentioning the word coronavirus itself. On the day of the Ball, February 1, I made a trip to Walgreens (ostensibly to buy something for my earache), and quietly purchased a 200-pack of vinyl gloves. I asked for hand sanitizer at the counter, but discovered that both Walgreens and the adjacent CVS had sold out.

That night, I left the box of vinyl gloves open on the check-in table, hoping that attendees would take and wear them. When I returned at the end of the event, the box was still completely full.

In some ways, chairing the Viennese Ball Committee in the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak gave me a deep insight into how other institutions, including governments and universities, must have reacted to the news. The initial confusion and bemusement: well, it’s just like a cold, isn’t it? Isn’t it also really far away from us? The hard constraints: training, purchasing equipment, and scaling everything up; the concern of sparking unnecessary panic; the general lack of solid information and precedent.

When you’re heading a large organization and facing an unprecedented new threat, every move you make impacts a thousand people. So you try to move carefully—but, as we see now in the age of pandemic, acting too slowly is itself a threat. Acting quickly, but then retracting your word, is also disastrous for your image. Suppose we had cancelled the Ball. California did not feel the effects of the pandemic until another four weeks later. For four weeks, we would have looked like idiots, facing mass backlash and steep financial repercussions. We had signed a contract with the hotel guaranteeing that we would pay them more than $30,000—and since the emergency had not yet revealed itself, we would have had to pay every penny.

Over the next several weeks, as the coronavirus pandemic unfolded, I watched the lessons I learned as the leader of a dance event re-emerge in the University’s own—at times cautious, at times contradictory, at times hasty—responses to the outbreak.

But in the meantime, life carried on. I scrambled to catch up on the deluge of schoolwork that had been delayed while I was focusing on running the Ball. I planned my Spring Break trips, booked flights. A paper that I had written for a group project had been accepted for a conference in Boston, and I planned to travel from there to go skiing with my boyfriend in Canada. I watched as my Google Flights Tracker prices ticked downwards, and when the moment was right, snagged 4 airline tickets (SFO-BOS, BOS-YYJ, YYJ-CVG, CVG-SFO) for only about $500. I did not buy insurance; this fact would become quite striking later, when I spent hours on hold with United Airlines and Air Canada, hoping cancel these very flights.

The rhythm of university life is such that it makes the problems of the rest of the world seem smaller—until they are too large to be contained. On February 25, the same day that Stanford sent participants in the Florence, Italy study abroad program home, I interviewed and was accepted for the class Hacking for Defense. I was unsure if I actually had room in my schedule to take the class, and this matter became the topmost pressing concern on my mind. I was constantly refreshing my email, it seemed, for a reply from the professors I had reached out to for advice.

On an utterly normal Tuesday, I had been biking to the Law School for a meeting when I ran into a former Viennese Ball Committee member. She was headed to Sweet Hall to talk with the BOSP (Study Abroad) advisors.

“Is it for your study abroad at Oxford next quarter?” I asked, knowing that she had been accepted to the program.

“Yeah, but I really hope they don’t cancel it.”

I brushed off her comment. “Cancel it? I mean, like, Italy is a concern, but not England.”

In hindsight, this statement did not age well.

By early March, talk about the coronavirus has finally breached its incubation period. On March 3, Stanford released a statement calling on us to cancelling events with more than 150 people. My mother sent me the link a few hours after I had already read the news.

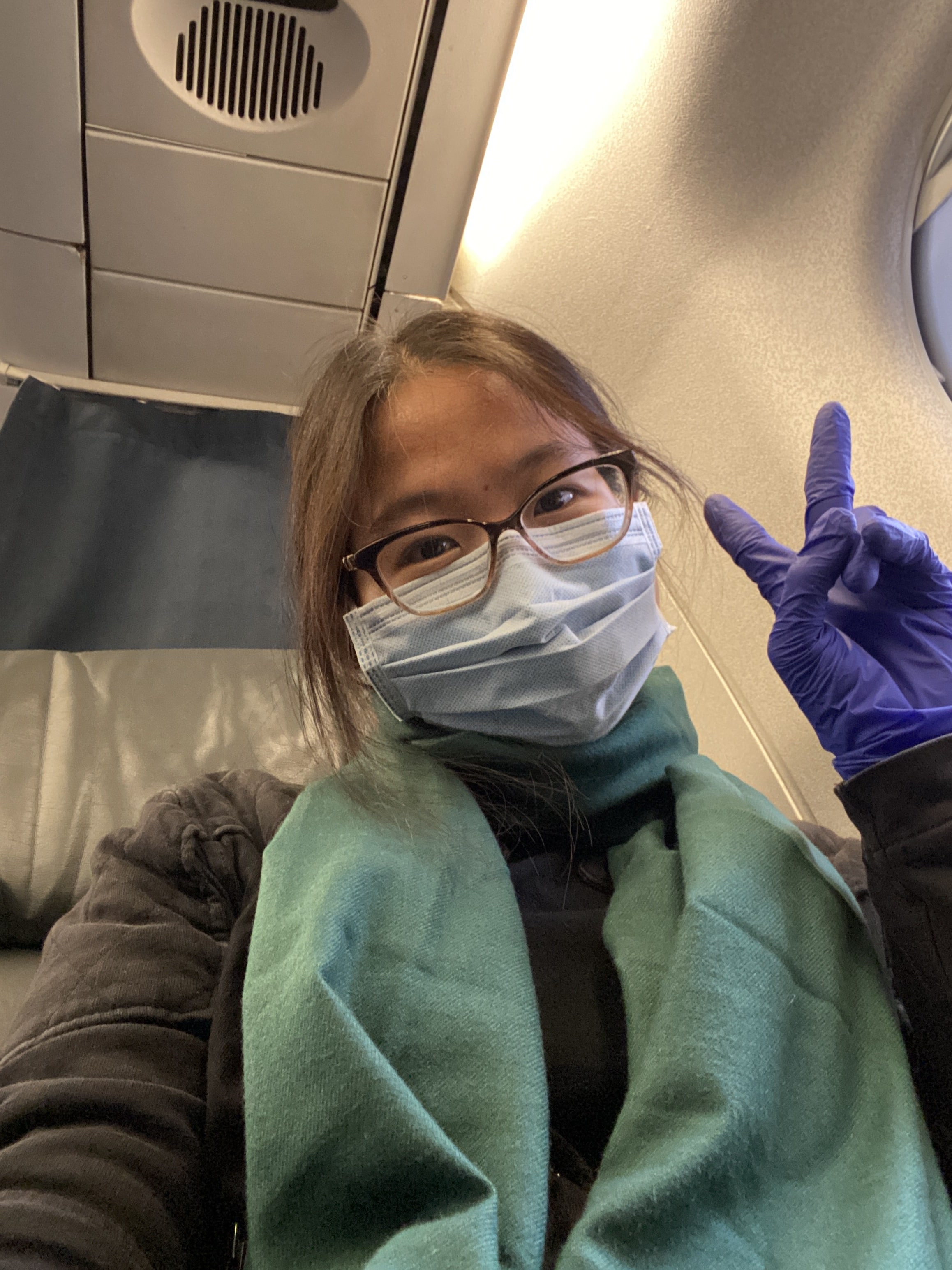

Yeah, holy crap, I texted back,

The next day, March 4, Stanford announced that it had cancelled all BOSP programs for the Spring. I thought back to my conversation a few weeks ago, horrified that I was now eating my own words. I have always been mildly germophobic, but I was now even more so. I replenished the bottle of hand sanitizer that I always carried around me, rubbing the clear liquid between my hands in an almost-compulsive manner. Otherwise, however, the steady drumbeat of life continued. On Friday, March 6, I met with a postdoc in my lab. “I think I’m going to fly out to Boston pretty soon,” she said towards the end of the meeting. “Why is that? Because of the coronavirus?” “I have nothing in my apartment here, whereas my husband has stocked up our place in Boston.” “Okay, makes sense,” I said, finally registering how close the coronavirus had come to home. For the first time, I sensed the panic and uncertainty sinking into my gut. I stared down at my own hands: did I have the coronavirus? Instinctively, I popped open my little bottle of hand sanitizer and let a few drops fall into my palm. What if it was just a matter of time? That afternoon, I took a nap. When I woke up around 8PM, my phone had exploded with notifications. Stanford had just made the last week of Winter Quarter classes remote. Friends were texting me: Does this mean we can go home now? All right, I’m booking a flight for tomorrow morning. Chaos and uncertainty ensued. Over the next several days, my inbox flooded. My friend made a graph of the emails she received related to coronavirus. The trend, over a week, was a steep exponential curve. Indeed, news of the cancellations spread faster than the actual virus did. The morning after the announcement of remote classes, high school friends based on the East Coast had sent me messages. I just heard the news. Are you ok? I spent an hour replying to everyone. Yeah, I’m fine. Things are just a little crazy right now. Finals were still on—just remote—and professors insisted that we show up for class on Zoom. “I’ll be asking about these topics on the final,” my NLP professor warned. And so, as Week 10 began, I mostly kept to my room, flitting between various Zoom meeting rooms. I glanced at the news from time to time, adopting an approach of ‘wait and see.’ I had never been one to act brashly in a moment of panic, and I figured that, since I still needed to take exams, it was more useful to be on the West Coast (where my classmates were), and in my dorm room (where I felt productive and set up). Travel would have also been incredibly disruptive to my ability to getting myself into a focused headspace. Over Family Weekend, just a week prior, my parents had visited me. They had brought me myriad snack foods and two types of instant noodles—a Tonkotsu ramen, and something else that just said “HOT” on the package. Though they probably expected the food to last me another quarter, I made a significant dent in the stash during my week of remote classes. While I played Zoom lectures in the background, I made instant noodles and nibbled on chestnuts. It bemused me that Family Weekend now seemed like such a normal snippet of college life, and now, just a week later, my world as I knew it seemed to be crumbling. Zoom lectures were surprisingly smooth, except everyone showed up as a black, muted square. I also turned my camera off, since I was typically sitting in my dorm room, still wearing pajamas, hair a tangled bird’s nest, and sported a noticeable red zit on my right cheek. In times when I did step out of my room—typically to grab an individually-plated meal from the dining hall to bring back to the dorm—I joked that my sense of style was “techie in quarantine.” I wore a mismatched getup of sweatpants, a T-shirt, a Microsoft jacket, and a surgical mask. Still, human resilience is an incredible thing. Students, well aware of the looming deadlines ahead, seemed to dig in and keep going. We adapted to the new normal. At one point, my friend set up his 20-inch monitor in the empty conference room, and the two of us watched Zoom lectures together—which gave me a sense of camaraderie and support, despite the directive of isolation. After that, I moved some of my work from my dorm room—where the blinds were always drawn and time in the artificial light stood still—to work in the conference room. A rotating cast of characters—mostly my closest friends—established that room as our own little domain. We generally sat a few feet from each other and bumped elbows in greeting, but it was still nice to see their faces and collaborate on projects in person. Socially, coronavirus dominated the conversation. Speculation about making Spring Quarter virtual swirled, which was especially concerning because most of my friends and I—all seniors—were set to graduate next quarter. Every few hours, it seemed, a new announcement or petition would hit my inbox. Thousands of students were writing petitions to allow students to remain on campus, to cancel finals, to better inform cleaning staff of coronavirus risks, among seemingly dozens of requests. The petitions were hosted on Google Docs that were so jam-packed with cursors that it overwhelmed Google’s system and prevented people from actually editing them. Still others reacted with humor. Online meme groups, like “Stanford Memes for Edgy Trees,” exploded with hilarious content that commented on both the tragedy and absurdity of our situation. I later joined a second meme group, “Zoom Memes for Self Quaranteens,” where someone had actually designed hoodies emblazoned with “Zoom University.” Tens of thousands of college students from across the world had joined the group. All of a sudden, it was as if every university student in the world attended the same school. Our suspicions were confirmed on March 10, when Stanford announced that Spring Quarter would begin virtually and recommended that undergraduates leave campus. By then, any illusions I had about staying on campus had entirely disintegrated. My Spring Break plans had long since disappeared, leaving but a handful of cancelled confirmation numbers behind. Now, it seemed, my more immediate plans were also on the chopping block. I texted my parents: Okay, looks like I’m going to have to come home now. I tried to leave the next day, but realized that I needed some amount of time to finish my group projects, pack my belongings, and say my goodbyes, and moved my flight to Friday morning. The mood on campus had turned apocalyptic: people drank wine in the conference room (it wasn’t allowed, but when would any of us see each other again?); I spent $70 in meal plan dollars, buying late-night food for 5 of my friends and two totally random people. When would I ever have the chance to spend it again? On March 10, the WHO declared coronavirus to be a pandemic. Friends began leaving campus, first in a trickle, and then in droves. I would look out of the window of the conference room from time to time and see another face I recognized. I banged gently on the glass to no avail, goodbyes still hanging on my lips. I cried—of course I did. At one point my puffy eyes were mistaken for being sick (fortunately, I did not have COVID-19). But eventually the sadness wore away into a dull resignedness. That's how the stages of grief work, or so I hear. In my final days on campus, I spent as much time with my friends as I possibly could. The last night before I left, two of my best friends came to visit me on West Campus. We all ate Late Night food—I had a matcha boba tea, which was too watery and certainly overpriced—and reminisced about our time at Stanford. The past week, we all agreed, had felt like a year. I let them stay until past 1AM, even though I needed to wake up at 7 for the airport the next day. I could still sleep when I got home, but my friends wouldn’t be there. At some point while I was packing my room to leave, another University email arrived. Finals were not cancelled, despite student petitions; we were to proceed as normal. The email barely registered in my consciousness. I continued peeling photos and keepsakes off of my wall, dusting them off, and placing them in a shoebox. I focused on the ball of blue tape in my left hand, at the old Christmas and Valentines’ Day cards in my right. I felt like I was literally tearing my life, and its memories, from the walls of my room. Final exams, petitioning to take classes, and planning out Spring Quarter—once top of my mind—seemed, for the first time, secondary. Indeed the University would later go back on this communication. The very next day, Santa Clara County announced that it would ban all gatherings of more than 30 people. The University subsequently ordered all undergraduates to leave campus (rolling back a previous policy that allowed undergraduates to stay), and mandated that all final exams be optional. When the morning came to leave campus, I wrapped a green scarf around my neck and tucked a surgical mask inside. Bearing in mind that Asians could be racially targeted for wearing a mask, I wanted the ability pull it down while I was waiting for my Uber (just in case the driver refused me a ride). I wore a pair of purple surgical gloves. I kept one bottle of hand sanitizer in my left pocket, and another in my right. Two more bottles of hand sanitizer were tucked into my carry-on. Then, I turned off the lights, and with a dull click, Winter Quarter was over. I was headed home. The lines at SFO were nonexistent. I made it to the front of the line so quickly that I fumbled my driver’s license. When I reached my seat on the plane, I found that I was sitting next to another Stanford student leaving campus. Behind me was a girl from Berkeley. The plane buzzed with the stories of a shared experience. Jackets rustled; luggage noisily crammed into overhead bins. Everywhere, the same awkward introductions: Where are you traveling to? Well, my university was made online… All of us, traveling with the same cloak of uncertainty, boarding the same one-way flight, wondering what to do with our freshly-uprooted lives, our dashed hopes, our virtualized connections. When I was accepted to Stanford, all of the incoming freshman were asked to read three books. Among these was a book called A Paradise Built in Hell—a nonfiction book about life during disasters. Little did we know that, for this soon-to-be freshman class, their own senior year would turn to Hell, and it would be up to them to build a Paradise in it.